The Magazine of The University of Montana

The Bakken Room

Oil Rush Keeps Many UM Alums Hard at Work

Story by Ed Kemmick, Photos by David Grubbs

A truck hauls oil away from a rig near Sidney.

John Olson has lived in Sidney for forty-eight years, so he’s seen oil booms. But he’s never seen anything like the Bakken boom now rolling across eastern Montana and western North Dakota. Sidney, whose population was pegged at 5,100 in the 2010 census, is expected to gain another 6,000 to 9,000 residents in the next few years. Three new motels are expected to open this spring, and their 225 beds will double the number available in Sidney. Apartments that rented for $300 a month barely a year ago are now going for $1,500 or even $2,000 a month.

There are obvious benefits for business people like Olson, who graduated from The University of Montana with a bachelor’s degree in education in 1962. He is the president and owner of Blue Rock Products, which distributes soft drinks and wholesale beer and wine in eastern Montana and western North Dakota.

“Our sales have gone right through the roof,” he says. “I guess we’re the number one Pepsi plant in the country right now, so we’re enjoying some notoriety.”

The downside is that office assistants who made $11 to $13 an hour a year or two ago now command $17 to $21 an hour. Truckers with a commercial driver’s license can make $80,000 to $110,000 a year in the oil fields, with overtime.

“It’s pretty hard to compete with that kind of situation,” Olson says.

And Sidney is not the epicenter of the Bakken boom. That would be Williston, just over the border in North Dakota. Its population has doubled since the 2010 census to reach 25,000, and projections are that it might hit 60,000 in three to five years.

In early March, North Dakota officially became the third-highest oil-producing state in the country, behind Texas and Alaska, and it is expected to overtake Alaska within a year. North Dakota had 6,600 wells producing oil in January, and the state has been flooded with job seekers from all over the country and beyond. In January, North Dakota had the lowest unemployment rate—3.2 percent—in the country. In second-place Nebraska, the rate was 4 percent.

TOP: Sidney has seen a significant increase in traffic on its main streets.

BOTTOM: A flare burns off gases near an oil rig in Richland County.

Olson says the scale of activity in Williston is hard to describe without seeing it for yourself. On a recent trip there, he says, he counted thirty-one semi-trucks lined up at one intersection, trying to turn onto Highway 2.

Tom Richmond, administrator of the Montana Board of Oil and Gas Conservation, was exaggerating, but not by much, when he described the housing situation in the Williston area.

“Those chicken coops are starting to look pretty valuable,” he says. “The chickens are going to have to find another place.”

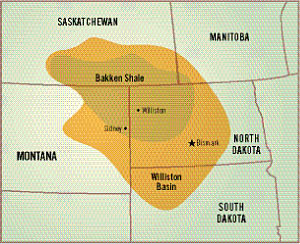

The Bakken is an oil-bearing formation that stretches beneath 200,000 square miles of Montana, North Dakota, and two Canadian provinces. It was named for Henry Bakken, the Williston-area farmer on whose land the formation was discovered. Vertical wells have been tapping the Bakken since the 1950s, but it would take another forty years for the right combination of technology to make it possible to really capitalize on the vast reserves of oil.

That combination involves horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing—the forcing of sand, water, and a mix of chemicals under tremendous pressure through perforated steel pipes thousands of feet underground. The “fracking,” as it is known, creates fissures in the rock, through which crude oil trapped in the formation slowly seeps out, ready to be drawn to the surface. Fracking is controversial in many parts of the country, but Richmond says in the Bakken, the deepest reservoirs of freshwater sit 7,000 feet above the layers where the fracking takes place.

In any case, if you combine the new technology with high oil prices—they were hovering around $105 a barrel in late March—you’ve got the Bakken boom. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates there are about four billion barrels of recoverable oil using existing technology in Montana and North Dakota.

Those kinds of numbers keep a lot of people busy, including many UM graduates.

The Bakken covers 200,000 square miles.

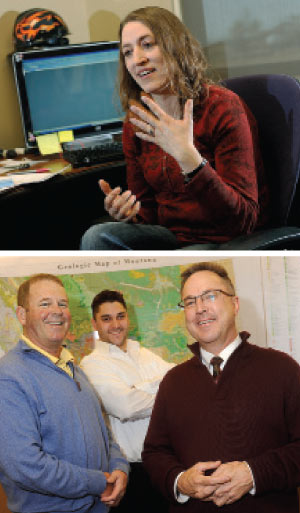

Layaka Mann, who earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in geology from UM, loves the excitement of the oil business.

“Anytime there’s a new, big thing, I want to be the first one there,” she says.

Mann says she stayed at UM to earn her master’s because she wanted to study under geology Professor James Sears. It was Sears who suggested in 2004 that she apply to work for Sunburst Consulting in Billings. She was the company’s eighth hire, and she spent her early years with Sunburst as a field geologist in North Dakota. She worked long hours many days in a row, and she was the consulting geologist on one of the first exploration wells in the new phase of the Bakken boom. It was a dry hole, unfortunately, but she got her opportunity “to be the first one there.”

Drilling in the Bakken is enormously complicated, and Mann’s job when she started was to interpret a steady flow of information coming up from underground and make sure the drill bit was staying on track.

“When you’re going two miles horizontally, two miles underground, you have to use a lot of data,” she says. “You have to make sure all the trends you’re seeing make sense. But by the time we get the information, the bit might be 100 feet ahead of the information you’re getting.”

She likened her job to driving down the interstate looking in the rearview mirror while trying to stay between the lines.

Mann is now a partner in Sunburst, which employs 125 full-time and contract workers. Sunburst also has nineteen UM-trained geologists on the payroll. Mann spends most of her time in the Billings office these days, but she knows she’ll get back in the field again.

“I’m waiting for that special project to come up that I can’t stand not doing myself,” she says.

Another UM graduate with a degree in geology, Patrick Montalban ’81, put himself through college by working as a roughneck during the summers. His father, Joseph, started as a roughneck in Alberta, Canada, and went on to establish several oil companies. Patrick’s son, also Joseph, a 2009 UM graduate with a degree in business marketing, was the one who pushed Patrick toward the Bakken.

| “ | Anytime there’s a new, big thing, I want to be the first one there. | ” |

Patrick spent so many years drilling for oil in Utah, Arizona, Colorado, and Texas, he never thought he’d get back to Montana and North Dakota. His company, headquartered in Cut Bank, now has an interest in seven wells in Sheridan and Roosevelt counties in northeastern Montana and two counties over the state line in North Dakota. The company also has acquired 24,000 acres in Sheridan County.

A friend of Montalban’s and a fellow ’81 graduate of UM, Carter Stewart, played a big role in discovering the western end of the Elm Coulee oil field in Richland County, where virtually all of the Bakken activity in Montana is centered.

Though the Elm Coulee is not as big as the plays in North Dakota, most of the 700 active wells in Montana are there, and some industry observers expect increased activity in Montana. As it is, taxes on oil and gas production in Montana brought in about $2 billion for local and state government from 2000 to 2011.

The Bakken boom has had a big ripple effect on the economy, creating opportunities for hundreds of other businesses and dozens of trades and professions. That was brought home to Billings Area Chamber of Commerce President John Brewer on a recent trip to Williston. Brewer says Target Logistics is the biggest operator of “man camps” in the Bakken. The company provides more than 3,000 rooms for oil field workers and has a staff of 350—chefs, housekeepers, builders, and maintenance people—to meet their needs. Target Logistics serves 9,000 meals a day, Brewer says, and he learned that most of those meals are provided by Sysco Food Services in Billings.

In addition, Brewer says, an engineering company in Billings is working on a 3,000-home subdivision in Williston. Partly because of the housing shortage, many Montanans, from Billings and all over the state, commute to the Bakken, often working for two weeks and then returning home for a week.

“It’s just like migrant workers working in Dubai,” says Patrick Barkey, director of the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at UM. “They’re working and shipping their money home.”

One indicator of the size of the boom, Barkey says, is a comparison of wage and salary disbursements across the state. The bureau tracks those figures in the seven largest cities in Montana, and in the rest of the state separately. Last year, nearly all the major cities performed below the state average, mostly because the oil- and gas-producing counties are doing so well. A growth rate of 4 percent a year would put a county in the top quartile statewide, Barkey says, and from the second quarter of 2010 to the second quarter of 2011, wages and salaries grew 16.2 percent in Richland County and 11.9 percent in Fallon County.

In Richland County in particular, Barkey says, “this has not been kind of a one-quarter wonder here. This has clearly taken off.”

TOP: Layaka Mann

BOTTOM FROM LEFT: Carter Stewart, Joseph Montalban, and Patrick Montalban

Barkey acknowledged that high gas prices, while good for the oil-producing counties, can put a drag on other sectors of the economy. But higher energy prices are still a net benefit for Montana because energy production is such a large part of the economy, he says.

Barkey says the Bakken boom appears to have some staying power, mainly because emerging economies around the world are adding great numbers of people to the middle class, creating an enormous demand for natural resources of all kinds.

Steve Ruffatto, an attorney with the Crowley Fleck law firm in Billings, says the Bakken boom does appear to be different from booms in the past, mostly because it is driven as much by advances in technology as by the price of oil.

But Ruffatto, a UM law school grad who focuses on natural resources and has been with Crowley Fleck since 1976, says he probably is more cautious than most people, having been through a couple of booms. Crowley Fleck, the biggest law firm in Montana and North Dakota, has been hiring in recent years at a time when many firms scaled back, and it now has thirty-five attorneys doing work in oil and gas development matters.

John Lee, chairman of Crowley’s energy department, remembers doing title work on what turned out to be the discovery well for the Elm Coulee field. It was also the first horizontal well in Richland County.

“It basically kind of snowballed as the technology evolved,” Lee says.

Despite the continuing boom, Ruffatto says he can’t help but be wary. “I just expect that circumstances will develop that will cause it to diminish,” he says. “I’m the one who’s saying, ‘This will pass.’ It’s a cyclical business.”

ABOVE: These man camps are set up near Trenton, N.D. The camps dot the countryside around the Bakken.

BELOW: Oil tanker cars sit at a rail facility near Trenton, N.D.

Over in Sidney, few people are trying to figure out how long the boom will last. It’s all they can do to deal with its everyday effects.

Olson, the owner of Blue Rock Products, mentioned “the horrendous increase in traffic,” new demands on law enforcement and schools, and the never-ending need for new roads and increased water and sewer capacity.

All the heavy truck traffic is crumbling roads in the county, Olson says, which takes a toll on his fleet of delivery trucks. And it’s so hard to find a mechanic in Sidney that he sometimes has to have his trucks towed 270 miles to Billings for repairs.

“The list goes on and on,” he says.

Cami Skinner can sympathize with Olson. A native of Dagmar in northeastern Montana, Skinner earned a business administration degree from UM in 2003 and an M.B.A. in 2006. She is now an agricultural and business banker for Wells Fargo in Sidney and, as of January, president of the Sidney Area Chamber of Commerce.

Skinner says the population of Sidney is still given as 5,000, but if you add the people living in RVs, nearby man camps, motels, and trailers, the population has been estimated at anywhere between 6,000 and 9,000.

Steve Ruffatto, left and John Lee are attorneys at Crowley Fleck in Billings who work on oil and gas projects.

Despite all the impacts on Sidney, Skinner says “in many regards, daily life seems very much the same,” while “every business, for the most part, is seeing growth.”

The school district is trying hard to keep up with the growth, and it is working with the city and county to accommodate all the growing pains, Skinner says, “but I don’t know if you can ever get ahead of the curve we’re in right now.”

In a part of the state that has struggled for decades with periodic drought, wild swings in agricultural commodity prices, and the persistent feeling that its needs are ignored by the powers that be in Helena, most people are unabashedly thrilled with the boom. You can put Mann, the consulting geologist, in that category.

“I can’t tell you how wonderful it’s been,” she says. “It’s given me the opportunity to stay in the place I love. And now I have the opportunity to offer other people that chance.”

Email Article

Email Article